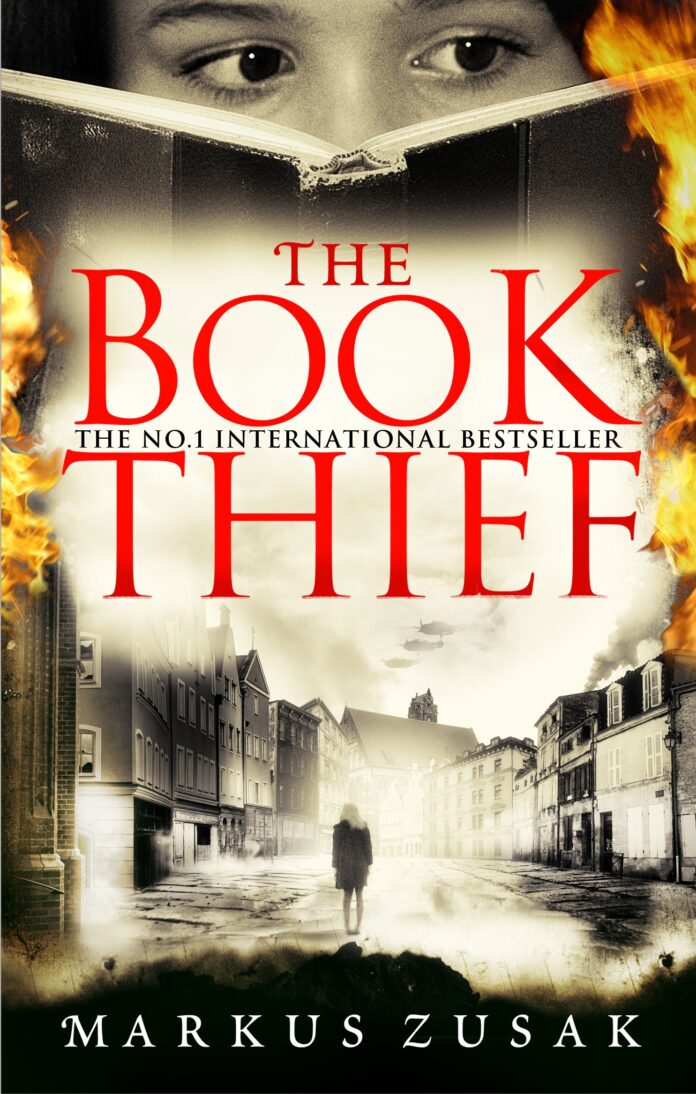

The Book Thief is a historical novel penned by Markus Zusak set in World War II that deliberates on themes of love, language, and mortality. Published in 2005, the book is Zusak’s signature and bestselling work, providing fresh insight and furthering our understanding of victims of the Holocaust.

Zusak was born in Australia to Austrian and German parents who had emigrated to the continent in the late 1950s. He went on to study history and English after high school and is the author of 6 books, including The Underdog, Fighting Ruben Wolfe, The Messenger, and Bridge of Clay. His most famous work is The Book Thief, an enterprise that received many literary awards and widespread recognition.

The book is narrated by Death, a quiet and morose voice, at times cold, at times caring. He describes scenes in vivid shades of colour with a sense of grim detachment but confesses that he is sometimes moved to act in sympathy with a human story.

The plot follows a young girl, Liesel Meminger, as she comes of age in Nazi Germany. She arrives at the home of her foster parents in Molching, a small town on the outskirts of Munich after her younger brother dies on the train journey there. She comes to them distraught and withdrawn, but quickly finds a friend in Rudy Steiner, a boy with bony knees, blue eyes, and lemon coloured hair, determined to have adventures and run races like his idol Jesse Owens. During her time with her newfound family in Molching, she is exposed to the horrors of the Nazi regime, caught between the naivete of childhood and the destructive nature of her surroundings.

As the political situation worsens, Liesel’s foster parents take in a Jewish fist-fighter called Max Vanderburg and conceal him in their basement to protect him from almost certain death at the hands of Nazi henchmen.

Liesel’s foster father Hans develops a close relationship with Liesel, teaching her to read and write. She also forms a bond with the town mayor’s wife Ilsa Hermann, who allows her to first read books from her private library, and later steal them.

Understanding the power of written word, Liesel begins to steal books that the Nazi party is seeking to destroy, eventually moving on to write her own story, one she shares with Max.

Hans draws the ire of Nazi officials when he offers a weak, suffering man a piece of bread during a march of Jewish prisoners towards the Dachau Concentration Camp. Consequently, his Worker’s Party application is accepted, and he is immediately drafted into the army, ordered to clean up the shrapnel and debris left in the aftermath of bombings. Max runs away, fearful of the consequences of Hans’ actions and the suspicion it will subject his household to. Leisel later spots him in a marching group of prisoners, ignores orders to keep away and joins him. She is whipped as punishment.

Hans returns safely home. Seemingly days later, bombs are dropped on the town, indiscriminately killing friends and family. Liesel is the sole survivor. She is devastated by her loss and refuses to clean the ashes off herself when the mayor’s family take her in. She returns to the river to say her goodbyes to Rudy and has an emotional reunion with Max when he returns to meet her. Death saves the manuscript she had written, deciding to keep it for himself. He peruses the volume and admits as much when he finally meets Liesel after she dies, an old woman in Sydney. He admits he is unable to comprehend the dual nature of humanity, the depths of its depravity and the sweetness of its compassion.

The Book Thief is incredible in the way it seamlessly weaves different book titles into its devastating plotline. The novel is divided into ten parts, each named after a book that Liesel acquired, ones that played a significant role in her life.

Part one is The Gravedigger’s Handbook, collected from the damp soil of her brother’s funeral, the first book that Liesel ever read with Hans’ patient guidance. Part two is The Shoulder Shrug, a book she rescued from the ashes of death. Mein Kampf is part three, though Liesel never read this piece of literature, it belonged to Max. The Standover Man was Max’s gift to Liesel, a book he had written and illustrated himself on the erased pages of Mein Kampf. The Whistler and The Dream Carrier were both stolen from Isla Herman’s library. Part seven is The Complete Duden Dictionary and Thesaurus. The book was actually a gift from Isla Herman, but Liesel considered her acquisition a theft.

The Word Shaker was another gift from Max, and the Last Human Stranger was another tome stolen from the library. Part ten is the climax, the finale, the Pièce de Résistance. It is The Book Thief, Liesel’s labour of love, the story of her life since her first encounter with written word.

All these stories played a part in Liesel’s life. Some of them were stolen by the little book thief, some were gifted, some were rescued from certain death. Isla Hermann left her window open for Liesel to come in for The Whistler. She saw the footprints in the library, knew that Liesel had come for the book, but let her come again anyway. In this way, Liesel ‘stole’ The Dream Carrier. Isla left the Duden’s dictionary as a present for her curious little thief, and later left her Christmas biscuits and The Last Human Stranger. The Word Shaker and The Standover Man were both presents from Max, handwritten manuscripts on whitened sheets of the Mein Kampf.

The Mein Kampf was originally Max’s book. Max details the irony of how the Fuhrer’s book had been the one to save him. He had detested the words, loathed them, seethed at them. The pages of extremist Nazi propaganda became blank canvases for his own thoughts and reflections. In this way, it was important to Liesel.

The Gravedigger’s handbook was stolen from the snow of her brother’s burial, the Shoulder Shrug from the fires of Jewish literature and Nazi hatred in Molching.

The last book was written by Liesel herself, a collection of memories right from when her brother died on the train, through her times in Molching with her foster parents Hans and Rosa, her days of frolic and thievery with Rudy, her moments hiding Max in the basement, watching out for him in the parades to the concentration camps in Dachau, right up until her night in the shallow basement of her home, when English bombs rained down on Molching, wreathing Himmel Street in halos of fire, suffocating its denizens in cloaks of ash. Her words had saved her from the fate of her family and friends.

I loved everyone in this book, a rare thing for me. But the people that stood out to me the most were Liesel’s parents.

Hans Hubermann – Liesel’s foster father – captured my heart when he wordlessly washed Liesel’s bedsheets after she once woke up traumatized and wet her sheets. The many days he spent painstakingly teaching Liesel the alphabet, deciphering page after page of the Gravedigger’s Handbook. His luminous silver eyes as he painted over Jewish slurs on the road of yellow stars, the way he kept all his promises even when they endangered his life. How he fed a dying Jew on the parade to Dachau, how he knelt to receive lashes for the deed.

Rosa Hubermann, stout as a cupboard, face like cardboard, hair stringy and elastic grey. The woman who defended Liesel when she first arrived, who in the same breath called her saumensch and made her collect the town’s washing. The woman who beat Liesel with wooden spoons when she disobeyed her, the woman who cooked atrociously, yet was the first person in the room to offer to feed a stranger, a wild-eyed, malnourished Jew on the verge of death. The woman who prayed silently with a soundless accordion for the return of her husband. The woman who comforted Michael Hopstafzel in the Fielder’s bunker. The woman who loved and loved and loved as she yelled and shouted and screamed.

Needless to say, this book made a huge impact on me. It has been the only book that I have read that has moved me to tears. I could not bring myself to read it more than once, since the words blurred and ran, cutting into my skin like barbed wire. Perhaps someday, I will read it again, appreciate all its twists and nuances, the bold colours, and the sweeping imagery, but that day is not today.

This book took a lot out of me, but it gave a lot in return. The wondrous perplexities of human nature, the goodness of human spirit, the ambiguity of what is right and what is wrong, all awash in a field of abstruse grey. How right prevails, just a little, even in the midst of great wrong.

As Death declares by the end of the book; ‘I am haunted by humans.’