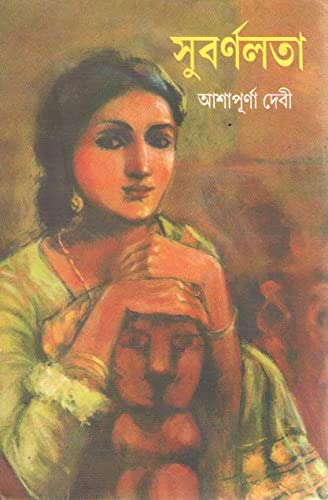

The culturally rich and prosperous land of Bengal has produced a number of talented writers and groundbreaking novels over the years. Famous authors like noble laureate Rabindranath Tagore brought Bengali literature to the fore. However, any discussion about Bengali literature would be incomplete without mentioning the contribution made by the female litterateurs. Even when penned by male authors, most female characters in Bengali novels were usually shown as women of substance and with a free mindset of their own. When women started representing themselves in literature, it not just offered a new perspective to the readers but also portrayed the struggles and dreams of a woman. The pioneer of feminist Bengali literature is undoubtedly, Ashapurna Devi.

Born into a very orthodox north Kolkata family, Ashapurna Devi’s whole life was spent amidst the four walls. Her writings describe the lives of the housewives in 19th century. She essays a time when Bengal Renaissance was slowly picking up pace and woman’s liberation movement is finding its roots. There were inhuman and archaic customs as well as social censures and women’s journey to self-discovery was full of inflexible patriarchal restrictions. There was also a hidden and ardent desire to break free from the shackles of society. Her magnum opus, “The Satyabati Trilogy” (“Prothom Protishruti”, “Subarnalata” and “BakulKotha”) is certainly one of the most popular and celebrated book series of Bengali literature. The three novels narrate the stories of three generations of women. Subarnalata is the second book of her maternal trilogy. In this book, Bakul recollects the story of her mother Subarnalata and writes the story of her mother to posit their struggle against the system.

THE CENTRAL THEME

Subarnalata fights to search for a space of her own within the male-dominated society. This search becomes a struggle against the existing patriarchal social structures which deny the existence of women as an individual who are different from their so-called social guardians. Society’s denial to grant her a free will and independence gives rise to another demand of the women— the creative space, which in the true sense becomes a real ‘space of her own’. Subarnalata starts to search for her creative space to express her locked up desires and to come out of her social cage. She ultimately becomes the true torch bearer of the feminist movement, which was initiated in her by her mother, Satyabati and she continues her war against the inhuman patriarchal system from the andarmahal (the inner house). The ‘dakshiner baranda’ (The south-facing balcony), symbolizes her dreams of an open space, where she will be able to live a free life and offer a better life for her daughter.

THE PLOT

Subarnalata learns about the endless struggle of the women to establish their unnamed identity amidst a patriarchal culture from her mother Satyabati. Since her childhood, she was introduced to the essential education of being a human being, not a woman. This contradicted with the social norms and sowed the seed of humanism in Subarnalata, with which she tried to judge every custom, be it social, religious or personal or even in her later marital life and raised her voice of protest against the sexual politics inherent in them. However, Subarna was forcefully married to Probodh Chandra and her untimely wedding came as a disaster to her life. Satyabati abandoned her family and went to Kashi in protest. Subarnalta had to painfully bear the burden of this daring act of her mother throughout her life with occasional taunting from her in-laws. But what Satyabati could do was quite impossible for anybody else.

She started the agitation in her own way by choosing the oddest bedroom for her. Although the other members of her family considered her to be weird and mentally challanged, Subarnalata succeeded in transcending the earthly desires of getting a home. Inspite of all these problems and tongue-in-cheek comments, her search for her own space continued. Intellectual stimulation came in the form writings of Rabindranath. Jaya didi gave Subarna books and magazines through the small hole in the wall. But her freedom was destroyed by her husband and she was compelled to go to the labour room several times. She even educated her children in the footprints of her mother and started coaching the little boys and girls of her family personally, which was mocked by her in-laws as “Mejo ginnir pathshala”. Unlike the other women of the family, who conformed to the laws of patriarchy and performed the duties of the family like good house wives, Subarnalata raised her voice and demanded a different atmosphere, where the woman will get the status to stand beside men in equal rights. She also advocates for the proper sanitation of the labour room which at that time was a luxury for the middle-class people to provide. But she is in turn insulted by Muktokeshi, which shows that how women who are indoctrinated to the patriarchal views are sometimes more tyrannical and crueler than the men. Women themselves become the representatives of patriarchy.

Apart from this, Subarnalata, being a common middle-class housewife proved herself to be unique by addressing and reacting to the Swadeshi movement that was starting in the whole country. The Swadeshi movement moved her and compelled her to participate silently from Antapur (The inner chamber). Subarna abandoned the foreign goods by burning all the new clothes for the Durgapuja. While, her in-laws were scared of this daring act of annoying the British, surprisingly, the maid servant supports her. She uses her unique attitude and novel outlook to analyse the difference in responses of the lower class and the middle class to the nationalist movement. She tries to inscribe her thoughts in her personal diary, where she writes about herself, about the condition of the women in the society.

Unfortunately, her dream of bringing up her children in her own light, for which she endlessly fought, was not fully successful. Her children always felt that her wishes and aspirations were peculiar, thus, they never understood her and maintained a distance from her. She realized that she performed the duty of a mother but lacked in affection. Subarnalata turned into a feminist role model from an ordinary Bengali woman. She became the true heir of her mother. Bakul is her only daughter, who looks into her mother’s life and tries understand Subarna’s journey . Bakul takes the responsibility of writing the story of her mother and grandmother first before writing her own. Though Subarna left no sign of her creativity, she succesfully sowed it in the heart of her daughter.

BIOGRAPHY OF ASHAPURNA DEVI

Ashapurna Devi was born on 8th January 1909 in a conservative Bengali Baidya family (physicians) in north Calcutta. Her mother Sarola Sundari, belonged to a liberal family and her father Harendra Nath Gupta was a famous artist. Sarola Sundari loved reading and she indoctrinated this passion into each of her children. Theirs was a joint family where the girls of the household were forced to remain uneducated while the boys were taught by private tutors. However, by regularly listening to the readings of her brothers/cousins, Ashapurna Devi eventually managed to learn the Bengali alphabets. Later, her father decided to relocate his family to a more spacious accommodation and in the new environment, Sarola Sundari and her daughters got ample scope to read to their hearts’ content. Although Ashapurna Devi missed out on formal education, she educated herself enough on her own. During the politically turbulent times, the girls of the Gupta household had minimal exposure to the outside world yet, they were aware of the upheavals and incidents taking place countrywide. This kindled a strong sense of patriotism in the heart of Ashapurna Devi.

At the tender age of 13, she secretly sent a poem named Bairer Dak to Sihu Sathi, a Bengali children’s magazine. Not only did the poem get published but the editor also requested her to submit more of her literary pieces. When she was 15, Ashapurna married Kalidas Gupta whose family lived in Krishnanagar. She had to balance household chores with her literary creativity. At the initial stages, she wrote only for children. Chhoto Thakurdar Kashi Yatra was well acclaimed in the genre of children’s literature. In 1936, she made her debut in adult fiction with her story Patni O Preyoshi was published in the Ananda Bazar Patrika. Prem O Prayojan, her first adult novel was released in 1944. During her lifetime, she composed more than thirty novels, poetry and ten volumes of collected works as well as children’s fiction. However, it was the trilogy, her magnum opus which catapulted her to fame and glory.

Ashapurna Devi was awarded the Jnanpith Award and the Padma Shri by the Government of India in 1976. She was conferred D.Litt by the Jadavpur, Burdwan and Jabalpur universities. Vishwa Bharati University,decorated her with Deshikottama in 1989. Apart from this, she also won a Sahitya Akademi fellowship in 1994. She passed away on 13th July 1995. Her literary works – translated in several languages – still remain part of school curriculum. The Indian Postal department issued a stamp on her – as a joint recipient of the prestigious Jnanpith award in1998.

Most of her literary works focus on gender bias (discrimination) and the sexist mindset of the society. Her short stories as well as novels vividly portray the emergence of the ordinary middle-class Bengali women – their repression, angst, growing awareness, awakening of conscience and the final revolt. Just like Subarnalata, she initially lived a cloistered life, devoted to reading, books were her doors and windows to the vast world that lay outside and she ultimately emerged as an ardent feminist.