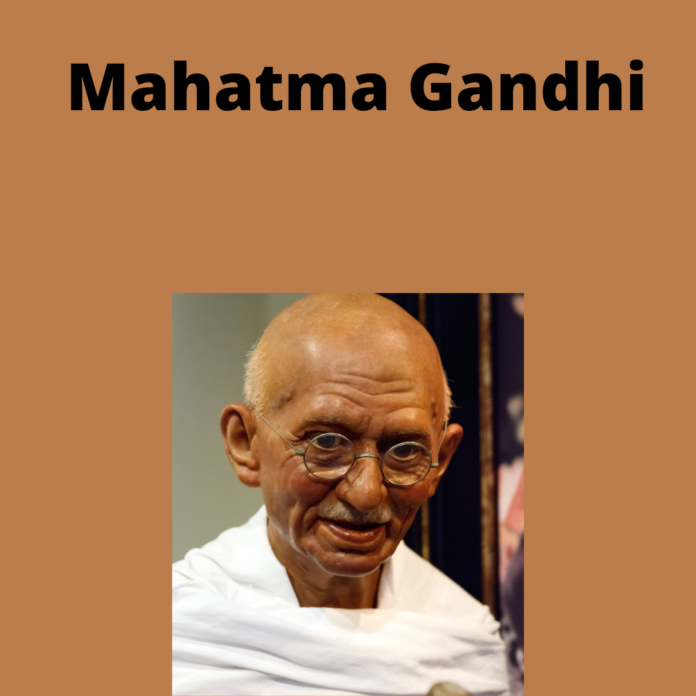

The father of the Indian nation, Mahatma Gandhi (Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi), said, “My life is my message.”

He was a leader of the nationalist movement, an Indian lawyer, political ethicist, anti-colonial nationalist, writer, and a kind-hearted person who battled for freedom against British rule.

Gandhiji graduated from the University of Bombay’s matriculation exam in 1887 and enrolled at Samaldas College in Bhavnagar. Maintaining the family tradition later he became a high office working person in the state of Gujarat. He continued his studies in London as he was not happy at Samaldas College so he accepted the offer and sailed to London in September 1888.

After reaching London, he faced difficulties understanding the culture and English Language. After some days after arrival, he joined a Law College named Inner Temple which was one among the four law colleges in London. It was not easy for him to get transform or to have a change in his life from the city of India then studying in college in England but he took his studies seriously and began to brush up his English and Latin. He met food faddists in England, but he also met people who knew a lot about the Bhagavad-Gita, the Bible, the Mahabharata, and other ancient texts. From all, Gandhiji learned more about Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity, and many others.

Many people were opposing the Victorian establishment from these people Gandhi slowly absorbed politics, personality, and new ideas. He passed his study in England and have become a Barrister but there was painful news for him when he was back to range in India, Gandhiji’s mother died while Gandhi was still in London. He was back in India in July 1891 and began his legal career but lost his first case in India, he realized that his profession was heavily overcrowded and he changed his mind and was offered a position as a teacher in a Bombay high school, but he declined and returned to Rajkot.

With the dream of living an honest life, he began to draft petitions for litigants but ended with the dissatisfaction of an area British officer. Fortunately, within the year 1893, he got a suggestion to travel to Natal, South Africa, and work there in an Indian firm for 1 year because it was a contract basis.

In the present century, children’s literature has not been a marginalized area within the world of literature. There is an extended list of such writers who are constantly writing for youngsters. As far because the beginning of the history of Indian English literature cares, writers have knowingly or unknowingly focused thereon. Rabindranath Tagore, R K Narayan, Mulk Raj Anand, and others are frequently credited with children’s literature.

however, the genre could not be developed as much during the pre-Independence period, but subsequently, several writers worked on it extensively. But not many big names except writers like Rushdie, Vikram Seth, etc. can be cited as far because the development of the genre cares. The article will, nevertheless, attempt to dispute Gandhi’s influence on a few pieces of Indian English children’s literature.

Gandhi is, without a doubt, the subject of many children’s novels.

Because of the limited scope of the magazine, it will concentrate on the children’s books recommended by the Bombay Sarvodaya Mandal/Gandhi Book Centre in Bombay.

B R Nanda’s Pictorial Biography of Gandhi, Uma Shankar Joshi’s Inspiring Stories from Gandhiji’s Life, Jyoti Solapurkar’s Gandhi, Ramanbhai Soni’s Story of Gandhi, Rajkumari Shankar’s Story of Gandhi, Sarojini Sinha’s A Pinch of Salt Rocks, and others.

will be taken for study. Some other works which are without the biographical account of Gandhi also will be taken. All these works are going to be studied with the aim of a literary analysis of the writers’ treatment of the technique, tone, and content, or length within the respective works. The paper also will attempt to scrutinize the books by age category, keeping in sight the divergent interests of youngsters of the age group 1-18.

It will also look at how children’s literature has changed significantly over time as a result of Gandhi’s influence. Undeniably, the influence of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi is often surveyed in most of the branches of data of the times. In terms of literary and visual portrayals of Gandhi, numerous research has been conducted. Harish Trivedi explores Gandhi’s depictions in this regard.

he writes:

Gandhi has pervaded Indian literature and the arts since his return from South Africa in 1915, and he may be found everywhere. From workplace walls to public locations to personal or transferred group memories He has been represented to enduring effect by a spread of foreign writers and artists also, from points of view that serve to illuminate him differently and sometimes with a striking supplementarity.

A few libraries, like the National Gandhi Museum in New Delhi, the Bombay Sarvodaya Mandal/Gandhi Book Centre in Bombay, and others, that are entirely dedicated to Gandhi, are frequently seen.

These libraries also have Gandhi-themed children’s literature. Gandhi’s and scholars’ writings, however, do not include comprehensive debates and literary analyses of Gandhi’s impact on this sector due to a lack of interest or understanding in children’s literature criticism. This is why works based on Gandhian ideas, such as Mulk Raj Anand’s Untouchable (1935), R K Narayan’s Waiting for the Mahatma (1955), and others, are rarely evaluated or considered as young adult fiction that falls under the category of children’s literature. There are a couple of books with visual references on Gandhi which will be helpful to know his life and beliefs for youngsters. But academicians don’t choose a number of those as pictorial books for our youngsters.

It has been a sophisticated task to define children’s literature. However, scholars like M Landsberg, J Rose, J R Townsend, N Babbitt, etc. have tried their best to define it keeping in sight various aspects of this literature. Generally, the meaning of children’s literature as ‘books which are good [in terms of emotional and moral values] for youngsters is taken by us (Landsberg, 1987). In other words, it encompasses those books or writings which are written by children, written for youngsters, chosen by children, or chosen for youngsters.

As far as its genres are concerned, based on methodology, tone, subject, or length of children’s books, this literature can be categorized into six major genres: picture books (board books, pattern books, concept books, and wordless books), traditional literature (myths, fables, ballads, ethnic music, legends, and fairy tales), fiction (fantasy and realistic fiction), non-fiction, biography or autobiography, and poetry (Anderson, 2006).

Based on the different interests of children’s ages 1-18, this can be divided further as picture books for pre-readers ages 1-5, Early Reader Books to develop reading skills for children aged 5-7, a chapter book for children aged 7-11, and young-adult fiction for children aged 13-18 (Jordan, 1998). This kind of division can differ from one country to another due to the differences in the language skills of non-native speakers.

In the world of literature, there is a long list of such writers who are constantly writing in all these genres for children. In this context, J K Rowling, Jacqueline Wilson, Anthony Horowitz, Lauren Child, Raymond Briggs, are some noteworthy figures. At the beginning of our Indian English literature, writers have knowingly or unknowingly focused on it.

Many children-centric works are often credited to Rabindranath Tagore, R K Narayan, Mulk Raj Anand, etc. Intending to get a discussion on a replacement literary history of post-independence Indian English literature, Makarand Paranjape tries to draw an image of up-to-date children’s literature in Indian English.

He writes:

The rise of children’s literature has been phenomenal. Several writers including Margaret Bhatty, Monisha Mukundan, Sirgun Srivastava, Swapna Datta, Loveleen Kacher, and Geetha Dharmarajan have enjoyed great success. Both Penguin and HarperCollins India have created new imprints exclusively for youngsters.

Finally, the boom has allowed tons more of Indian fiction to be translated into English than ever before. Some of the newer writers widely available in English now include Nirmal Verma, Srilal Shukla, Rahi Masoom Raza (Hindi), U R Anantha Murthy and K Purnachandra Tejasvi (Kannada), Vilas Sarang (Marathi), Gopinath Mohanty (Oriya), O V Vijayan (Malayalam), and several other others.

At now, it’s remarkable that the Indian independence movement and therefore the great Indian figures who fought for the liberty of India, Gandhi, Nehru, Subhash Chandra Bose, Bhagat Singh, have much influence on Indian English literature (particularly on post-independence Indian English Literature). And children’s literature in Indian English isn’t an exception. As far as Gandhi, ‘the man who has something for everyone, is concerned, Indian children in the latter part of the twentieth century learned about him in a variety of ways. Several books are written in the different genres of children’s literature.

In the present paper, the chosen books are being taken for discussion to watch the writers’ ways of bringing Gandhi to a toddler of today. It is interesting to look at how the authors retell his inspiring story so that he’s not just a part of a lesson.

Gandhi: A Pictorial Biography, by Bal Ram Nanda, was the first pictorial biography of Gandhi, published in 1972.

The historical significance of happenings and facts is separated into thirty-four chapters, with an index, and is illustrated with black-and-white photographs, newspaper clippings, facsimiles of letters, and cartoons.

“Childhood,” “Off to England,” “Briefless Barrister,” and “Briefless Barrister” are the titles of the chapters. Predictive language is full of long and complex sentences.

On several occasions, the author utilizes comparable language.

Here are a few lines from the book: Gandhi had been on the political stage for more than fifty years when he was shot by three pistol shots in January 1948…

“It is possible that future generations would scarcely believe that such a one as this ever walked upon the world,” Einstein observed of Gandhi in July 1944. He bathed with a stone rather than soap and scribbled his messages on scraps of paper with pencil stubs he could barely hold between his fingers…

For anyone over the age of 14, the book can be used as a ‘chapter book.’

The Story of Gandhi (1969) by Rajkumari Shanker can alternatively be classified as a ‘chapter book.’

However, the language and style differ slightly from the previous one.

It is recommended for children aged 8 to 14.

The story is told in simple lines with a short and snappy style by the author: Mohandas Gandhi was born on October 2, 1869, in a little white-washed home at Porbandar, on the coast of Kathiawad in western India.

Karamchand Gandhi and Putlibai Gandhi were his parents.

He was little and black, and he didn’t stand out among the many other Indian children. For an early book reader, reading Sandhya Rao’s Picture Gandhi (2007), which contains biographical details of Gandhi’s life, is often an alluring temptation (5- 7 ages).

She not only blends ancient black and white images of Gandhi with colorful hand-done pieces to show the facts, but she also utilizes language and style that is appropriate for youngsters.

On the first page of the book, she writes: “Among these are Joseph Lelyveld’s Great Soul, Ramachandra Guha’s Gandhi Before India, Rajmohan Gandhi’s The Great Boatman, Judith M. Brown’s Gandhi: Prisoner of Hope, and others.” Once upon a time, there was a man who lived such an unremarkable life that he died pennilessly.

He was a peacemaker who believed in the power of love and truth.

Once upon a time, this man was a young boy, just like any other.

He was a writer from a young age, and he enjoyed writing novels. He has published several books.

Autobiography of Gandhi, The Essential Gandhi, Hind Swaraj, and Other Writings, Gandhi’s Words, Satyagraha in South Africa, and many others are among the most well-known. Many authors have written on Gandhi, including Joseph Lelyveld’s Great Soul, Ramachandra Guha’s Gandhi Before India, Rajmohan Gandhi’s The Great Boatman, Judith M. Brown’s Gandhi: Prisoner of Hope, and others.

Thought balloons (a graphic convention used in the book to allow words to be understood as expressing the thoughts of a specific character) are also used to summarise various occurrences in Gandhi’s life.

These balloons appear to be peering inside his head.

The Story of the Dandi March (1999) for children aged 8-11 and My Gandhi Scrapbook (2007) for pre-readers aged 1-5 are two more Gandhi books contributed by Rao. ‘Pictures clipped and pasted, remarks tossed in, things copied from someplace, random thoughts, quibbles, and scribbles’ made up my Gandhi Scrapbook.

It could be considered a ‘wordless book.’

There are a few other books that feature Gandhi’s motivating anecdotes.

Some notable works include B Z Qudsia’s Our Bapu (1955), M Meghani’s Gandhi-Ganga (1968), Uma Shanker Joshi’s Stories from Bapu’s Life (1973), S Sinha’s Pinch of Salt Rocks (1985), Rita Roy’s Everyone’s Gandhi: A Collection of Gandhi Columns (1997), Ravindra Varma’s Gandhi: A Biography for Young People and Beginners (2001 ), Mrinalini Sarabhai’s Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2007) are some noteworthy works. Gandhian themes have also been given to children through poetry and play over the years.

Little Plays of Gandhi (1991) by Mulk Raj Anand was a fascinating book for children.

There are fifteen scenes in the book.

In dramatic discussions, each scene demonstrates Gandhi’s brilliance.

Scenes are set in the Sabarmati Ashram, where Krishan Chander Azad is brought down to earth from Bloomsbury’s posh snobbery.

And so He Plays His Part is a chapter from Anand’s novel. Makhan Gupta’s The Apostle of Non Violence: A opera (1987), Pratap Sharma’s Sammy: A Play in Two Acts (2005), Premshankar Trivedi’s Gandhi (2001), etc. may be taken as another remarkable dramatic presentation of Gandhian thoughts for youngsters. As far as Gandhi’s representation in Indian English poetry cares, it’s been a difficult task to possess a study on this subject. M K Naik’s remark in this regard is noteworthy: Astonishingly, the Gandhian whirlwind generated no outstanding poetry of any kind, even though the poetic arena remains as densely filled as before.

In his book Gandhian Myth in English Literature in India (1996), B A Pathan expresses a similar viewpoint.

It’s becoming increasingly difficult to find poems for children in Indian English at this point.

Some notable poems about the site for Indian youngsters include “Father of the Nation,” “Mahatma Gandhi,” “The Recipe,” “Glory of India,” “White Light,” and others.

Different aspects of Gandhian ideology also find circumlocution in several ways in several novels of Indian English novelists. Mulk Raj Anand’s Untouchable (1935) depicts Gandhian thought on the dignity of labor with the assistance of a young character Bakha. In R K Narayan’s expecting the Mahatma (1995), Gandhi appears formally because of the protagonist. He is at Malgudi. With the assistance of fictive characters just like the orphan-girl Bharati and Sriram, Gandhian thoughts are expressed by the novelist.

Furthermore, there are few books on Gandhi which may be taken as children’s literature by children. Understanding Gandhi through Cartoons (2009) compiled by Sharad Sharma may be a book of that sort. Through this book, children have contributed many cartoons/ comics on Gandhi’s life also as on its relevance and importance within the present era. Certainly, this type of innovative approach towards Gandhi confirms his relevance and importance within the present context for the post-independence generation. Mahatma Gandhi Struggled considerably from his youth but no matter all the suffering, he made his way. And he’s a really important part of our history of independence. One of his written books: an autobiography “The Story of My Experiments with Truth”, is a window to the workings of Mahatma Gandhi’s mind – a window to the emotions of his heart – a window to understanding what drove this seemingly ordinary man to the heights of being the father of a nation – India.

Starting with his days as a boy, Gandhi takes one through his trials and turmoils and situations that molded his philosophy of life – going through child marriage, his studies in England, practicing Law in South Africa – and his Satyagraha there – to the early beginnings of the Independence movement in India.

He did not aim to write an autobiography but rather share the experience of his various experiments with truth to arrive at what he perceived as Absolute Truth – the ideal of his struggle against racism, violence, and colonialism. As Gandhiji says, Live as if you were to die tomorrow. Learn as if you were to live forever. I have learned through bitter experience the one supreme lesson to conserve my anger, and as heat conserved is transmuted into energy, even so, our anger controlled can be transmuted into a power that can move the world.