The very phrase “book and author” is complementary like the angles that sum up to 90 degrees and incredibly analogous to ‘creation and creator’. Would the world not be sawdust without our books and authors? It is only a fair confession that perhaps no other opportunity can take a reader to cloud nine and the incrementing clouds like the opportunity to write about a book that we probably love more than ourselves.

To be just be able to talk about this author, with a distinguished reverie and profound pride that runs in my veins deeper than my blood, has taken the face of a lifetime achievement.

One and all, Amitav Ghosh! one of the best Indian writers and significant global thinkers of the preceding decade, holder of two lifetime achievement awards, the Padma shri and the Jnanpith, and four honorary doctorates, this man continues to expand his horizon, transcending all age and literary barriers, equally appealing to all the readers throughout the globe. Born in Calcutta, the city of joy, growing up in India, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka and completing his education from Dehradun, new Delhi, Alexandria and eventually earning a doctorate from the oxford university, his walk of life began with his debut novel, in 1986 “The Circle of Reason.”

He carried on with his formidable conquests with his ensuing, sensational literary pieces, in fiction, for instance “ The Shadow Lines”, “the Calcutta Chromosome” ,”The Glass Palace” ,”The hungry tide” , “The ibis trilogy” and “Gun island” and in non-fiction, for instance, ”In an antique land” , “Dancing in Cambodia and at large in Burma” ,”Countdown” ,”The Imam and the Indian”and “The great derangement: climate change and the unthinkable”. Both his fictional and non-fictional narratives sail subtly through different countries and continents, escorted by Bengali and south Asian culture. Beyond Latin and Greek, this connoisseur of literature speaks to his readers in a diction that can only be fathomed by the soul.

His writings entrap you into the euphoric sphere of realism and romanticism, making you traverse through past and present, love and loss, communal and political history, travel and diaspora, struggle and violence. Seeking shelter from the humdrum hustle bustle, under the pages of his literary creations, is what makes life more of an escapade.

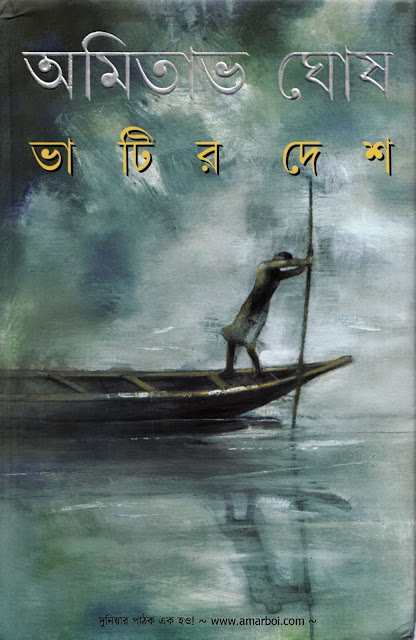

It is not every day that one comes across a book that will slowly and ever so sensually burn in them even after decades of reading it. Lacerating the deepest corners of your mind, inundating the chambers of your heart with the ebb and flow of a powerful tide, named “emotion”, magnetizing it with a sudden upsurge in intrepidity along with the abiding urge to dive deeper and deeper into the heart of nature are a few of the myriad intensities that the book “The hungry tide” stirs you with. Where time and tide blend, fresh water and salt mixes, where invisible is the brim between humans and nature, where hostility prevails as much as beauty and present is a very thin line between life and death, in the deepest of the interiors of the Sundarbans; an immense archipelago of islands, interposed between the sea and plains of Bengal from the Hooghly river in west Bengal to the shores of the Meghna in Bangladesh, is set the story of “the hungry tide”, with the collision of characters of different worlds, woven into an intricate fabric against the landscape of “The Bhatir Desh” or the tide country, amidst the lush universe of the mangrove trees in a way like never imagined before.

In “PART ONE- THE EBB : BHATA” , awaiting for us, in the threshold, are two of the most significant protagonists of the story; Kanai Dutt, a chivalrous and self-centered forty-two years old man who believed himself to be a “connoisseur” of women, translator and interpreter by profession, on his way to Lusibari, the farthest island of the Sundarbans to visit her aunt, Nilima Bose on an urgent and affectionate plea to unravel a packet addressed to him containing some writings of his long dead uncle and Piyali Roy aka Piya, a stout- hearted, adept and amicable young cetologist of Indian-American descent, in her twenties, with close cropped black hair and dressed in loose cotton pants and an oversized white shirt, on her way to Canning, the railhead of the Sundarbans, for her survey on the marine mammals, especially the Gangetic and Irrawaddy dolphins ,brought together under different circumstances but united in the journey to the same destination, the Sundarbans. Through a crisp but gripping encounter inside the train bound for their destination, where Piya commences a conversation with Kanai, after she had unintentionally “chosen to scald him with her tea”, the readers find themselves fazed in anticipation of how these characters would find each other again, as Kanai invites Piya to visit Lusibari before bidding each other a poignant goodbye, as they turn to different directions from the Canning station.

The narrative oscillates fluidly between Kanai and Piya. Kanai is shown fondling over recounted fragments of various colloquy with his uncle Nirmal from the days when he first set his foot in that familiar Canning station, more than thirty years ago from the present day to his last inadvertent encounter with his uncle in 1970, where Kanai discreetly bought his uncle a book with his own money, since the latter did not possess the means. Walking to his now frail seventy-six years old aunt, Nilima Bose aka Mashima, widow of Nirmal Bose, founder of the hospital in Lusibari and heads the organization that runs it, the Badabon Trust, Kanai delineates her as “almost circular in shape and her face had the dimpled roundness of a waxing moon.”

He begins to take in the sooty vicinity, taken aback by the once most formidable Matla River which was now no wider than a ditch. In between the present conversation and past recounting, a little light is thrown on Nirmal’s death; how he had retired as headmaster some months before his death and used to disappear without a word around the time of “Morichjhapi incident” and was one day found standing right on that embankment of Canning shouting “The Matla will rise”, his incoherent answers, mention of the packet of writings that he had left for Kanai and dying just after a couple of months of pneumonia. Another detailed flashback of Kanai takes us to the 1970s where a young fisherman, Horen, from the nearby island of Satjelia, then in his twenties but a married man and father of three children, comes to the rescue of Kanai, Nilima and Nirmal for taking them home and also mentions of his gratitude towards Mashima for all that she did for a girl, Kusum of Horen’s village.

A translucent glimpse into such characters dominating the past hinted at a much larger puzzle yet to be solved. Amitav Ghosh’s extraordinary wizardry is at play throughout the volume.We are taken into the deep interiors of Canning where a determined and strong-willed Piya makes her way to the rivers for her survey with an officious forest guard and a Mej-da whose behavior not only unsettles Piya but also made her doubt her choices. Meanwhile Kanai, who is brought to Lusibari, recalls the earthworks of the place through the reminiscing of his conversations with his uncle.

With Kanai’s reminisces on the trail, we are taken back to a vigilant Piya interrupted “when a distant fishing boat drew a scratch across Piya’s line of vision.” A few quite chaotic actions involving poaching, gun, the fisherman and his little son, Piya falls into the muddy brown water takes place. Readers grow angst by a drowning Piya only to regain their composure when “a pair of arms appeared around her chest.” Her knight in shining armor appears in the shape of a lean, stringy limbed fisherman with a narrow and angular face, dressed in no more than a faded rag that gave his skeletal frame “a look of utter destitution.” Not a single reader was left untouched by the unanticipated emergence of such a solicitous and benign character, who is later revealed to go by the name Fokir. Piya decides against going back to Mej-Da’s launch. Tipping the guard and Mej-da off with a considerable sum, Piya chooses Fokir and his launch and an evidently ‘happy to oblige’ Fokir, along with Piya and his little son Tutul, rows away.

In their way to the trust’s compound where Kanai was to stay, he and Nilima engage in a conversation about one of the trainee nurses of the hospital in Lusibari, Moyna Mondal and how her perturbing husband, who is revealed to be Fokir, has supposedly gone missing again, and this time, with their son. Fokir is unveiled to be the son of Kusum who was the only friend Kanai had in Lusibari back when he was young. Kusum had been killed when Fokir was no more than five years old.

In Nirmal’s study, Kanai finds the packet, Nirmal had left for him. He was surprised to see nothing but a long notebook, which was covered in Bengali lettering in Nirmal’s hand, inside the packet. With the date “May15,1979,5:30” and directly saluted to Kanai, the letter read that it was written on an island on the southern edge of the tide country; Morichjhapi, where Nirmal was residing as a guest in Kusum’s hut around whom the written story was pivoted. A leftist intellectual and writer of promise, Nirmal Bose was teaching in Ashutosh College when his path crossed with Nilima. Mesmerized and drawn by Nirmal’s “fiery speeches and impassioned recitation” and the light of idealism in his eyes, a resolute Nilima manages to find a seat next to him on the bus one day and in 1949, they get married, despite much opposition from Nilima’s family. After no more than a month of their marriage, the police came knocking at the door at the door of their tiny flat in Mudiali, owing to Nirmal’s participation in a conference convened by the ‘Socialist International’, in Calcutta.

His being detained for a day left him unsettled to an extent of dormancy. At the mercy of her father’s bidding, a couple of doctors was sent to Nirmal who suggested an environment change for him. After a sojourn in Gosaba, they made up their minds to settle in Lusibari, ending up there in 1950.They were dumbfounded by the destitution, hunger and the catastrophe of the tide country along with its concomitant issues of storms, floods and diurnal deaths. Nilima’s observation of a startlingly large proportions of widows, her inquisitions revealing the belief that the girls of the tide country were raised with: “ if they married, they would be widowed in their twenties- their thirties if they were lucky” and their imagining of early widowhood, led to a revolutionary and practical Nilima to sow the seeds of the “Women’s Union” and ultimately to the foundation of the “Badabon Trust”; “Badabon” being the Bengali word for ‘mangrove’, a word that Nirmal loved. Fokir and Tutul’s bathing each other and laughter and Piya’s unvoiced gratefulness towards all of Fokir’s offerings, all that he honored her with; from humanity, solicitude to soap cake and a sachet of shampoo, that was on the island “a treasure of a kind”, scintillated the nightfall.

Looking back at 1970, at one of the Lusibari Women’s Union meetings, Kanai meets Kusum with “close cropped hair” and in a “tattered red frock” for the first time. Kusum was brought in Lusibari by Horen and put into the custody of “Women’s union”, from the evil clutches of a landowner, Dilip Chowdhury after Horen got to know that Dilip, who offered employment to Kusum’s mother, taking her away with him to Calcutta, was into a gang that was involved in trafficking in women. Kanai’s growing proximity with Kusum went on proliferating over the days of their togetherness. The story shifts to the folklore of the Sundarbans; Bon Bibi, when one day, Kusum and Kanai go to see the stage performance of “The Glory of Bon Bibi.”

The folklore revolves around the divine Bon Bibi and her twin, Shah Jongoli being chosen for the divine mission of travelling from Arabia to “the country of eighteen tides”, the sphere of which was ruled by Dokkhin Rai, a powerful demon-king, a man named Dhona and a young lad named Dukkhey, who carried the curse of misfortune and how Bon Bibi showed the “Law of Forest” to the world: “The rich and greedy would be punished while the poor and righteous were rewarded.” After seeing a riveted Kusum with a bleared visage, Kanai acted on his impulse to console her, but his fingers instead of finding hers get entangled in the folds of her frock, accidentally encountering a soft and warm part of her body, leaving them both electrocuted. Kanai managed to halt a stumbling Kusum who then narrated to her how she called Bon Bibi too, the day she had seen her father get ripped apart by a tiger but Bon Bibi never came. Overwhelmed with unknown emotions, Kanai “brushed her tears with his lips” and “wanted his body to become a buffer between her and the world”, but most of all, he was overcome by the intense urge to hold her in his arms and protect her. Their treasured bubble of love ruptured almost as soon as it was formed with the interruption of a panting Horen, who had come to take away Kusum since Dilip and his men were in Lusibari, looking for her, only for Kanai to never see Kusum ever again.

Back to present day, Piya recalls fragments of her childhood; the full-throated quarrels of her parents phrased in Bengali, her mother’s diagnosis of cervical cancer, her shutting out everybody but Piya and the smells of her home. Later, hearing Fokir hum, she encourages him to “sing louder.” In the moonlit midnight, somewhere in the river, entangled is Piya and Fokir’s heart, despite their “inescapable muteness,” where a shivering Piya finds herself comforted by a worried Fokir until all her clammy sensations dissipate, with the ignition of a more intense flame. No sooner did it dawn upon them, than they untangled in embarrassment. Piya is met with a new day by some muffled grunts, which could only mean on thing; The Irrawaddy Dolphins, Orcaella Brevirostris, a group of which decided to halt near Fokir’s boat. Piya begins making her detailed survey on the dolphins while Nilima narrates to Kanai about “TheMorichjhapi Incident” of 1979. In 1978, a great number of people, originally from Bangladesh, fled from a government resettlement camp in Central India and came to Lusibari in the hopes of a little land to settle on. The Government forces, however, with their declaration of Morichjhapi as a reserved forest were unbending in their determination to evict the settlers.

This led to a final clash in Mid-May of 1979; The Morichjhapi massacre, exactly the time period during which Nirmal wrote his letters. Nilima later reveals to Kanai that Kusum was killed in the massacre. At noon, Kanai meets Moyna. Moyna takes Kanai to the hospital, where he is touched and moved by Moyna’s evident pride in the institution and takes an instant liking to her as her ambitiousness and aspirations reminded him of himself. After returning to the guest house, Kanai begins reading another page of the notebook which brings forth an angst Nirmal, whose heart was filled with the trepidation of what was to become of him without his school, pupil and teaching after his near approaching retirement, who lied to Nilima about writing poems and who had abandoned his great pleasure: Reading. An invitation from an old acquaintance demanded him to visit Kumirmari.

At the embankment, Nirmal encountered Horen Naskor and asked him to give him a ride to Kumirmari in exchange of getting Horen’s son enrolled in his school. Horen was more than happy to oblige with his “Saar”. With Fokir’s boat brought to Garjontola, a confounding entangled greenery, Piya, fokir and tutul makes it to the Island’s interior with a slightly disbalanced Piya, saved from falling face forward by an amused Fokir. He and Tutul perform a strange little ritual, that closely resembled Hindu rituals but with a chant that contained a word: “Allah,” much to Piya’s confusion. On their way back, Fokir shows Piya pawprints of a tiger and added to that, Piya hears an “exhalation” antecedent to her sight of an adult Orcaella swimming with a calf. In the boat, sitting in Fokir’s companion, surrounded by the quiet breathing of the Orcaella against the backdrop of Fokir’s “alternately lively and pensive” melodious humming, all the barriers of language were transcended, there existed no culture, faith or religion; just two human beings, Piya and Fokir, who conversed in a language that can otherwise only be perceived by the soul. Kanai continues reading the notebook that read how on Nirmal’s way back to Lusibari from Kumirmari, he and Horen were confronted by a raging storm and decided to take shelter in Morichjhapi where “unexpected fate” brought them at the door of a shack only to be revealed to be belonging to Kusum and the then four years old Fokir.

Upon questioning Kusum how she ended in Morichjhapi, she began relaying to them how she had ended up in Dhanbad first, where she met a good, kind-hearted man, Rajen, who not only let her stay in his own shack but also brought her news of her mother who was sold by Dilip to other traffickers, took her to see her mother and later asked her mother to let him marry Kusum. Three months after Kusum’s marriage, her mother had passed away and four years hence, she lost Rajen too when a train had begun to move with Rajen still unpaid. Kusum decided against staying in Dhanbad and finally ended up in the tide country, Morichjhapi. Meanwhile in the treacherous rivers, Fokir throws himself at Piya just in time to save her from a Crocodile hiding itself well beneath the surface of water, in which Piya’s wrist also happened to be submerged. After rowing furiously for some twenty minutes, Fokir manages to take the boat to a sheltered place when he and Piya assents to their heading for Lusibari now.

“PART TWO- THE FLOOD: JOWAR” of the book sets in motion with Fokir bringing Piya to Nilima aka ‘Mashima’, in Lusibari and immediately walking away without a goodbye, leaving Piya with “an icy feeling of abandonment.” Piya recapitulates how she met Fokir and had been saved by him repeatedly. Nilima cordially invites to stay over in the guest house of the compound. Unbeknownst to all the readers, Fokir, Piya, Kanai and Moyna, the tides of their lives were about to change in a way nobody could have prophesied. Kanai’s eventual unravelling of the journal of Nirmal leads to the glory and terror of what the past beheld to resurface, the dots to be connected and the parallels of love and loss of the past to that of the present to be reflected. Nirmal, as it turned out, had begun to see a new life of revolution in Morichjhapi that lured him in and not even Nilima’s admonitions could deter him. Piya goes to Kanai, in the hopes of catching up with her cordial host when she meets Moyna for the first time, admitting to find her “quite beautiful in a way.” The shift in the narrative is marked by the readers overhearing a dulcet conversation between Nirmal and little Fokir, who addressed each other as “Saar” and “Comrade” respectively.

While Nirmal went on with his fascinating story-telling of the badh(embankment), storms, rivers and tides, earthquakes and crabs, little Fokir reciprocated his fascination with his own curious set of questions. Present-day, Piya and Kanai visits Fokir and Moyna, Piya attempts to pay Fokir as a way to confess her gratefulness, but forestalled by Moyna, Piya gives it to her, much to her unwillingness. With Kanai as the translator, Piya relays to Fokir that she needs his help for the continuation of her and if he could make the arrangements for returning to Garjontola Pool. To her relief, Fokir happily complied. But Piya frowned upon how dismissive his own wife was of him, how much she belittled him. In 1979, Kusum had come to Lusibari, to Nilima seeking her help in the setting up of medical facilities in Morichjhapi. Nilima’s reluctance and bland refusal in getting involved fumed things up between her and Nirmal.

Nirmal “felt himself torn between his wife and the woman who had become the muse he’d never had”. The plot at this point takes up acceleration with the possible implication that Nirmal was powerfully drawn towards Kusum, that he had already given in to the revolution he had tasted in her and the simultaneous conspicuous attempts of Kanai at flirtation, with Piya as he says,” I’d say someone like you would be much more to my taste.” With Fokir’s interruption about the already arranged “bhotbhoti” and Piya’s leave to organize her stuff, Kanai dives back into his Uncle’s Notebook where the past anecdotes were inching closer to the “Morichjhapi massacre”. Kusum, Horen, Nirmal and little Fokir’s visit to the Garjontola for Bon Bibi puja, where Kusum and him pointed out to Nirmal that dolphins were “Bon Bibi’s messengers”, discloses to all the readers Fokir’s proximity with the dolphins and why the rivers were in his veins. Piya and Kanai heads out to see the arranged ‘Bhotbhoti’; “THE MEGHA” whose sole owner turns out to be Horen. Piya’s elation and excitement spread through the readers’ hearts.

Nilima tries to discourage Kanai from following Piya into the forest, being concerned about her nephew, and talk him down by stressing on the statistic of the daily death, one at the very least, in the Sundarbans. Upon realizing that his whim has everything to do with Piya, Nilima gives up and just warns him to be careful. Back to 1979, the condition in Morichjhapi worsened with the police ordering the settlers to leave the island and return back to the shore from where they had come, the unforeseen defiance and determination to not leave Morichjhapi. The settlers left Nirmal bewildered and in absolute awe! As if on cue, the official motorboats picked up speed and came shooting towards the boat full of settlers, throwing them into the water. To Nirmal’s giddy relief, Kusum and little Fokir were not there in the boat. The siege went on for multiple days, despite the collected efforts of the settlers. The readers’ hearts almost halted by the brutal condition of the settlers as described: “…food had run out and the settlers had been reduced to eating grass. The settlers were drinking from puddles and ponds and an epidemic of cholera had broken out.” The wan and wasted form of Kusum affected Nirmal to the extent where he was forged into a state of sickness. Toned with the symphony of the emotive and evocative history of such predominate personages of the story, is the present-day expedition of Piya, Kanai, Fokir and Horen with “The Megha” pulling away from Lusibari. Preceding this, was the conversation between Moyna and Kanai where an insecure and envious Moyna confesses to Kanai her profound relief upon finding out about his decision to join the expedition, given that Piya and Fokir would not be alone. Despite a little fall-out between Piya and Kanai, when he condescendingly said, “if I hadn’t been here to tell you, you’d have had no idea what he’d seen,” they bond over again.

Kanai’s “calm and urbane” presence besides his talent of translation, proves to be quite propitious for Piya. Not only did she become more appreciative of his presence, but also a bond of affection and trust curves itself out. Kanai decides to finish reading the notebook. The reticent history follows Nirmal’s eavesdropping on Nilima’s conversation with a doctor and making out that the attack on Morichjhapi was no more than a heartbeat away. Nirmal,having escaped from his home, headed out for Satleja and finally to Morichjhapi along with Horen to rescue Kusum and little Fokir. The notebook ends with a cliffhanger: Kusum refusing to leave Morichjhapi, Fokir being taken away to Satleja by Horen and Nirmal’s firm decision to linger around in Morichjhapi as he put it, “I have to stay because there’s something I must write.” Kanai, who shuddered with the end of the letter no more than the readers did, made his way to Horen who was sitting outside on the deck in the hopes of reaching to the end, only to become acquainted with the knowledge of how the assault began the very next day of Horen’s leaving with Fokir; women, among whom Kusum was one, being used and thrown into the rivers to be washed away by the tides and as for Nirmal, he was put on a bus along with other refugees who were sent back to where they had come from, fortunate as he was, they must have dropped him somewhere from where he found his way back to Canning, only to die after a few months. Piya pleads to Kanai for a favor: “To do some spotting” of the dolphins for her along with Fokir.

Fokir’s playful essence around Kanai, their man to man talks and inciting him to investigate the fresh claw marks alongside him, Kanai’s falling face forward in the wet mud, his fit of rage, sending Fokir away and an encounter with a tiger were precedent to Piya, Fokir and Horen’s coming to the rescue of a terrified and injured Kanai. Later that night, Kanai tells Piya about his plan to leave for Lusibari and finally for New Delhi the next day at daybreak. Before his departure, Kanai gives Piya a present. The unanticipated turn in the ambience of the story with the air being “stagnant and heavy” did not go unnoticed, finally following Horen’s prediction of an upsurging storm. Worried about Piya and Fokir, Kanai makes an urgent plea to Horen to head back to Garjontola. The already unsettled pace grows more perturbing with Piya and Fokir’s discovery of the carcass of the baby orcaella and Kanai and Horen’s state of angst and helplessness upon not finding them. Somewhere in the treacherous rivers, two hearts find themselves burning slowly and diffidently, drawn towards each other like all of the gravity existed nowhere between them with a shared glimpse of the lunar rainbow at nightfall, Fokir’s reaching for Piya’s hands and holding it in between his and Piya’s acceptance of Fokir’s offering her a plate of rice and spiced potatoes, even though spices were always harsh on her, it was as if “ a hand hidden in the water’s depths were writing a message to her in the cursive script of ripples, eddies and turbulence.” Overwhelmed and in need of a distraction, Piya began reading Kanai’s letter for her that read how the emotions (for Piya) that have generated in him were of “shocking novelty” and how he wanted to give her something that he knew only he could: A translation of the song “The epic of the tide country” that Fokir was singing, a song that lived in him.

A postcard on the back of the letter containing an excerpt of Rilke upheld how truly Kanai has fallen in love with Piya. As if on cue, the tide of emotions rises even higher when Horen asks Kanai if he is too blind to see that Fokir is in love with Piya too and he could have made it to Garjontola if he wanted to. Horen also discloses how the present milieu is just a recurrence of what had once already happened in the past; Nirmal being in love with Kusum just as much as Horen was, her entering Nirmal’s blood as much as Horen’s and how before the killing, she had chosen Horen over Nirmal, giving him profound proof of her love. Observing the erratic pattern of behavior of the Irrawaddy dolphins, Piya and Fokir becomes aware of the storm. As for Kanai and Horen, they helplessly head in the direction of Lusibari.

As Kanai was wading through the embankment with the hope that he would make it to the guest house, for an unguarded moment, he looks back at the ‘bhotbhoti’ to immediately get knocked sideways into the water by the wind, with the notebook bobbing in the current for some time before finally sinking out of sight. With the gale growing stronger and more violent, Piya and Fokir were fortunate enough to reach Garjontola. Leading her deeper into the island, he chooses a Mangrove tree as their shelter spot, tying them together to a sturdy branch, with Piya sitting astride it and Fokir behind her. With time, the winds only turned more violent and suddenly as if a dam had broken over their heads, they were atleast 9 feet below the water. After long, with the trough of the water catching up and a little subsiding of the water just in time for the tree to snap almost upright and their heads were above the water. With the change in wind direction, Fokir’s body was the only shelter for Piya.

The next day, ‘The Megha’ carrying Kanai, Horen and Moyna has covered two-thirds of the distance to Garjontola when Fokir’s boat was sighted, to reveal a crumpled Piya alone. Piya recounts how in the last hour of the storm, Fokir had been hit by an uprooted stump too hard with only the sari keeping them attached to the trunk and before the breath faded on his lips, he had whispered Moyna and Tutul’s name. Fokir’s body was brought to Lusibari and cremated. Towards the end, an unforeseen bond of affection and friendship forms between a broken Moyna and Piya, united in the grief. Piya tells Nilima about her plan of taking on a project, that she thought of naming after Fokir, in Lusibari under the sponsorship of the Badabon Trust, with Moyna as her partner. In the final peroration, Piya calls Lusibari “home” because for her, “Home is where the Orcaella are”, bonded together with a laughing Nilima who says, “Home is wherever I can brew a pot of good tea.”

Perhaps, the greatest reticence of this story lies in the upholding of the verity that we are but slaves to nature, in the portrayal that no matter how dominant we think ourselves to be, we are ultimately tossed and turned by nature’s hands just like chess pieces being controlled by a player. A mosaic of environmentalism, folklore, regional and political history, conflicts, poetry, love, revolution, wildlife, marine life, language, faith, idealism and reality, it truly leaves you famished for more. As riveting as the name “The Hungry Tide” appears to be, it is a trope for how the tides of our own lives are akin to the tides of the rivers; It can build like it can destroy. What Rilke once said, “we, who have always thought of joy as rising … feel the emotion that amazes us when a happy thing falls’, can it not be acquainted with love too? Through tosses and turns, Amitav Ghosh keeps Love to be the greatest conqueror, like the tides of nature.

Paralleling the love between Kanai, Piya and Fokir to that of Nirmal, Kusum and Horen, he paints that no language, faith or culture can form a badh(embankment) to hold back the tide of love if it rises; that nothing is as powerful as two souls, with entirely different melting points, that melt into each other. Amitav Ghosh’s adroitness in the conspicuously portrayal of the animals being the closest associates of nature is marked since the beginning. Beyond everything, “The Hungry Tide” resurrects the buried revolution in our heart and makes us question our identity and our place among the almighty nature. In short, this book holds the power to deracinate an individual from his comfortable beliefs. As much as we hope “The Hungry Tide” to feed our hunger, it only leaves us famished for more.